Created by Matt Helders and James O’Hara, Ambulo is an all day café blurring the boundaries between cultural space and relaxed community hangout.

Here at The Mindful Rambler, we talk a lot about interpretation, storytelling, and sharing experiences, often through cultural lenses. So naturally, as a museum/arts professional who cares a lot about engaging the public, I’m always thinking about more ways to explore the theme of visitor experiences. Last month, all day café Ambulo opened its first location in Sheffield, UK, and in following the café’s updates on social media, I was impressed by how successfully they’ve been sharing their story. Each of their Instagram posts is an invitation to the public – to everyone – to join them in the space and enjoy their visit.

Arctic Monkeys drummer Matt Helders and The Rockingham Group co-founder James O’Hara, who have been friends for years, conceptualized Ambulo and have seen it through to its opening. They collaborated with Museums Sheffield to launch two locations; the first at the Millennium Gallery, and the second opening soon at Weston Park Museum. Alongside its setting in a cultural space, Ambulo’s welcoming vibe makes it an ideal example of visitor engagement done right.

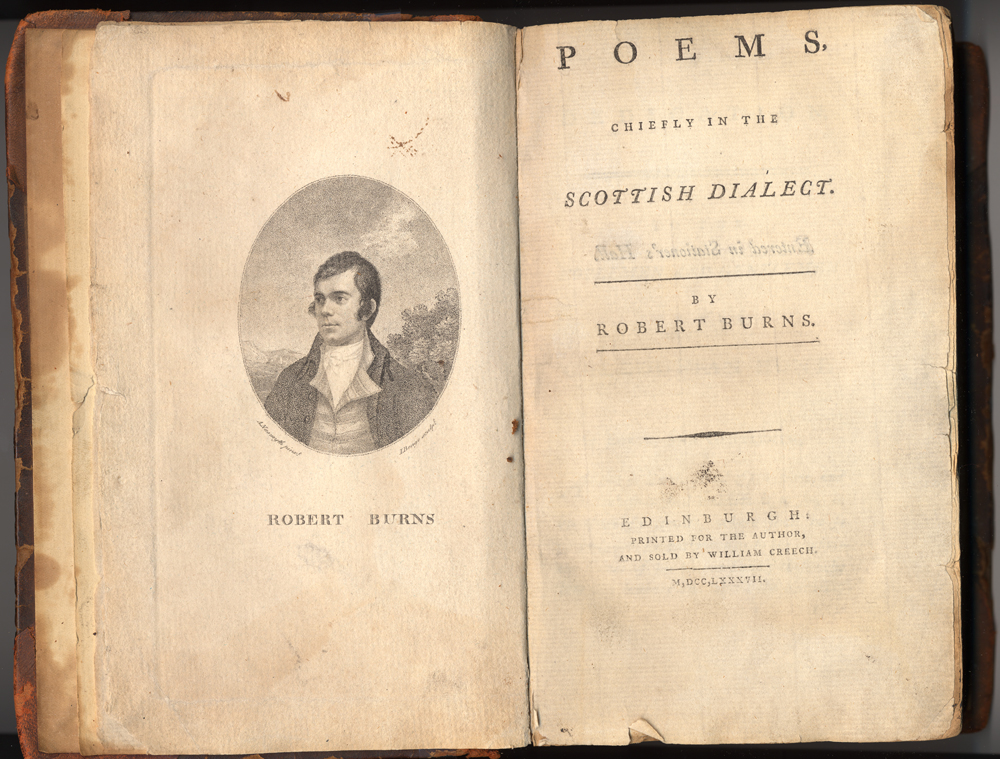

Interestingly, “ambulo” means “to wander” in Latin, just like “ramble” means “to wander” in Middle English/Dutch. Ambulo and The Mindful Rambler seem to have an inquisitive outlook in common, and I was eager to explore this idea of learning and sharing in more depth. I recently spoke with James O’Hara, one half of the Ambulo duo, to hear more about the vision behind Ambulo, the significance of its location in museum/gallery sites, and how they’ve opened a café with inclusion as their priority.

Serena Ypelaar: What kind of visitor experience did you envision when you created Ambulo? Who is the space for?

James O’Hara: Our background with our previous ventures was very much more bar orientated and more focused on a late night offering. It was a very conscious decision with Ambulo to make a really light, open, inclusive space. There’s a definite feeling of responsibility that comes with providing a multi-faceted café in what is essentially the ground floor of a gallery.

SVY: Can you tell us about the partnership with Museums Sheffield and how Ambulo ended up in the Millennium Gallery?

JO: Essentially via a tender process. We were the only local independent to make it to the final 5, the rest were national operators with a much more experienced background in these sorts of spaces. However, I think our history of cultural engagement in the city (I’m the co-founder of Tramlines music festival) and our track record of transforming interesting, somewhat derelict buildings (Public is located in a former gents toilet) excited Museums Sheffield and our enthusiasm for the project balanced out the obvious risk element associated with choosing a smaller company like ours.

SVY: You and Matt spent a couple of years wandering and testing food and drink to inform the creation of Ambulo’s menu. How was that creative process, and what did you learn?

JO: The idea for Ambulo started over 3 years ago – or at least the concept did – Ambulo means ‘to wander’ in Latin, and mine and Matt’s travels have formed a big part of the inspiration for the food and the brand. The main takeaway is that our favourite places and experiences don’t disguise themselves in pretension or opaque terminology. Our aim is to democratise the dining experience and provide great produce across our food and drink without all the associated nonsense that can often come with it.

SVY: From food/drink to music to decor, there are many aspects to creating Ambulo as it exists now. Can you tell us about your collaborations with friends and local businesses?

JO: We have a core group of collaborators who we have worked with on almost all our projects. Rocket Design (Ben Pickup) make and build all our interiors, Totally Okay (Nick Deakin) has designed all the branding and associated imagery of this project and all our previous businesses, India Hobson takes all the photos, Swallows and Damsons have done all the beautiful floral displays and New Phase LED do all our lighting design. We’ve done so much together that we all have a real shorthand and understand how each party works. They’re an amazing group of people.

SVY: What’s your favourite dish on the menu, and why?

JO: I would say the Kedgeree Soldiers. It feels like a very Ambulo dish – originally an imported breakfast dish from Victorian times, Exec Sheff has put this through a prism of modernity to come up with a really delicious and simple reinterpretation.

SVY: Thanks for taking the time to speak with us! I’m looking forward to following Ambulo’s future programming, and I can’t wait to check it out in person one day soon.

Ambulo is now open in the Millennium Gallery, 48 Arundel Gate, Sheffield, UK. The café’s second location is slated to open at Weston Park Museum, Western Bank, Sheffield.