The Toronto Maple Leafs and the Montreal Canadiens haven’t met in the NHL playoffs since 1979. That same year, a pivotal work of Canadian Literature was published: Roch Carrier’s The Hockey Sweater. Whether intended or not, the story reveals an age-old culture clash between Ontario and Quebec.

Have you read The Hockey Sweater (1979) by Roch Carrier? If you grew up in Canada and had parents even mildly invested in hockey, chances are you have.

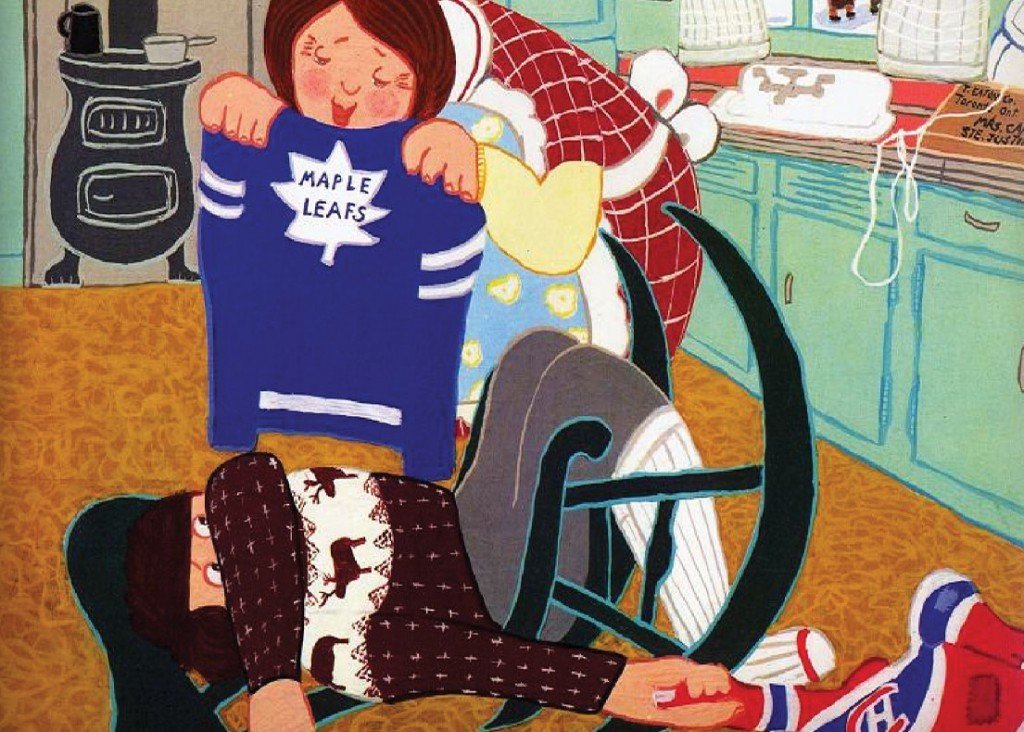

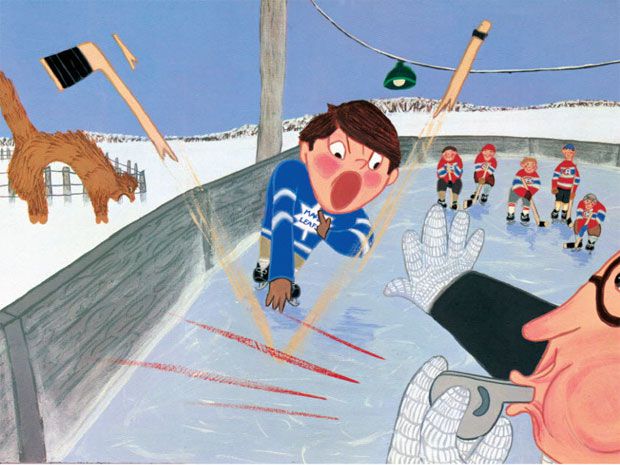

Titled Le chandail de hockey in its original French, it was illustrated by Sheldon Cohen and translated into English by Sheila Fischman. The story is enjoyed across Canada, among anglophones and francophones alike. It’s a children’s book about a young Roch Carrier growing up in Sainte-Justine, Quebec, who – along with every kid in his village – loves the Montreal Canadiens and wants to be just like Maurice Richard. In the winter of 1946, Roch’s Canadiens sweater becomes too small, and his mother orders him a new one from “Monsieur Eaton” (of the family behind Eaton’s department stores). After a mishap with the order, Roch is sent a Toronto Maple Leafs sweater. How will he cope with the stigma of wearing the wrong jersey?

Now seems like the perfect time to be writing about The Hockey Sweater. This year’s Stanley Cup playoffs are underway in the National Hockey League (NHL). The Toronto Maple Leafs are facing the Montreal Canadiens in the first round for the first time since 1979 (incidentally the same year The Hockey Sweater was published). The Maple Leafs vs. Canadiens rivalry is the oldest in Canadian hockey history, as they were the only two Canadian teams in the NHL’s Original Six from 1942 to 1967. They have met 16 times in the playoffs: Montreal has won the matchup eight times and Toronto has won seven (potential eighth underway tonight? knock on wood).

Unlike the Leafs, who have only won the Stanley Cup once in 1967, the Canadiens – nicknamed “Habs” in reference to Habitants, the early French settlers of Quebec – have won it 24 times, more than any team in NHL history. Yet despite this discrepancy, the rivalry between the two teams endures. How does The Hockey Sweater help preserve it?

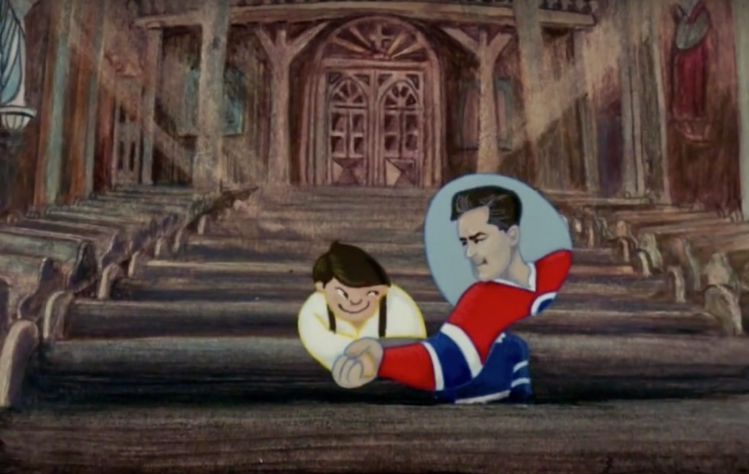

The Hockey Sweater was adapted into an animated short film for the National Film Board of Canada in 1980, with Carrier narrating his childhood story in both the French and English versions. The film was animated by Montreal-based illustrator Sheldon Cohen, in keeping with the aesthetic style of the picture book. Carrier had a long career in storytelling, receiving the Order of Canada in 1991 and serving as National Librarian of Canada from 1999 to 2004. He helped unify the National Archive and the National Library with Ian E. Wilson, the National Archivist at the time.

Full disclosure: born and raised in Toronto, I’ll always be partial to the Leafs, albeit in the most passive way possible. We were by no means a hockey family when I was growing up (and still aren’t). My uncles and cousins are big fans, and while my dad also loved hockey growing up, his true passion is soccer. He raised us with that love of soccer, so that’s what we know best. At the same time, my parents enrolled my siblings and I in the Leafs Buds Club, the official kids club of the Toronto Maple Leafs, when we were little. We got to go to Leafs practices and chill with the Leafs’ mascot Carlton the Bear. (I think I’m more invested in Carlton than I am the actual hockey… he’s just so cute!)

So how come my family and I, along with countless anglophones across Canada, have always loved this little book even though it scorns the Leafs?

Kids have grown up with the story regardless of their favourite teams because it resonates as a cornerstone of Canadian culture. We can all identify with team rivalries in general, especially in childhood. The Hockey Sweater is incredibly funny and offers a glimpse into life in Quebec during the 20th century. But beyond being a fun piece of Can Lit, it’s also emblematic of wider cultural implications between English Canada and French Canada. And although we might not have known it at the time we read or watched it, we as children were internalizing a key element of Canadian culture from a young age.

To put it simply, Canada’s post-European contact history is rooted in the French and the British battling over the traditional lands of Indigenous peoples. Ultimately, the Battle of the Plains of Abraham was a decisive victory that paved the way for the British to take over France’s colonial presence, unilaterally establishing British North America to add to their existing American colonies. The ensuing tensions between French and English culture in what would eventually become Canada – from language to religion – set a precedent for the strained interplay between French Canada and English Canada today.

The Hockey Sweater illustrates that cultural clash, whether or not it intends to (more on that later). Despite being a straightforward retelling of the author Roch Carrier’s childhood experience, many critics and readers consider it an allegory for the French-English divide. The issue is complex, and goes beyond the simple act of wearing hockey jerseys, but we see in the story that the Quebecois culture is fiercely defended within society. Roch is not permitted to play hockey with the others while wearing the Leafs sweater; both the referee and young curate discipline him for his lack of conformity. “Just because you’re wearing a new Toronto Maple Leafs sweater, it doesn’t mean you’re going to make the laws around here,” the curate tells him. He’s sent off the ice to go pray in the church, where he asks for the most important thing on his mind:

“I asked God to send me right away, a hundred million moths that would eat up my Toronto Maple Leafs sweater.”

The Hockey Sweater (1979)

And so ends the book. It’s punchy, and drives two points home: first, the sense of being othered for non-conformity, especially in a cultural context (Ontario’s team vs. Quebec’s); and second, the fact that hockey rivalries run deep in Canada, and it’s been that way since the NHL first started.

But whatever The Hockey Sweater may show us about Canadian culture, Roch Carrier insists that he wasn’t trying to make a political statement or promote Quebec nationalism. Instead, he was simply sharing his personal experience.

“I never tried to portray Canada to anyone. I’m just a storyteller. I’m interested by the experience people have and everybody has personal experiences, and everybody has limited experiences about something but that’s what life is made of.”

Roch Carrier at St. Andrew’s College, 2015

There isn’t really a moral to the story. In a children’s book you might expect a lesson about not being embarrassed to be different, or how it doesn’t matter what you wear (Roch’s mother actually says the latter in the book and film). But the young Roch maintains his dislike for the blue sweater. There’s something so endearingly unapologetic about his adamance that readers can’t help but love. As I said before, I’m inclined toward the Leafs even though I rarely even follow hockey, yet I’m not offended by this book at all. It represents a specific point of view and it’s funny. Sports rivalries will always persist, and trying to end them would be futile – we wouldn’t want it any other way.

The Hockey Sweater and its film counterpart are considered standout works within the Canadian canon for a reason, somehow transcending heated cultural (and athletic) frictions to become well-loved across the board. Roch Carrier’s story is strongly emblematic of Quebecois identity, culture, and sport, but the story’s themes are broadly appealing. Sheldon Cohen’s illustrations are stylistically memorable. The whole package manages to be quintessentially Canadian.

Regardless of whether you’re a Leafs fan, non-Quebecer, anglophone, or all of the above, you can still relate to those feelings portrayed in the book and animated film. We all understand the pressures to conform – sometimes we derive comfort and community simply from the act of conforming. As humans, we’re always seeking connection, and identifying with something that represents home makes us feel united.