Oscar Wilde, the Irish poet and playwright known for his unmatched wit and, infamously, for his sexuality, defined what it is to be unapologetically proud.

There were no Pride parades in his day, but Oscar Wilde’s openness on the streets of London arguably comprises the Victorian equivalent.

Growing up in Merrion Square in Dublin (which I just visited last month), Wilde moved to London and settled there for much of his life. He’s celebrated as a gay icon, but it’s little known that he was once in love with the woman who would become Bram Stoker’s wife, Florence Balcombe. Wilde was devastated when she chose to marry Stoker over him. He proposed to two other women before marrying Constance Lloyd, with whom he had two sons. It’s said that Wilde loved Constance, though of course he’s best known to have engaged in relations with numerous men. Today we’d probably call him bisexual, but Wilde considered himself “Socratic” when it came to love.

Wilde was proud of his identity – and quite open with his sexuality especially by the standards of the time. Yet even he had to hide who he was to avoid persecution in the form of a criminal trial. In 1895 Wilde was convicted of gross indecency, a homophobic law in the United Kingdom which made same-sex relations illegal for men.

Wilde wasn’t officially out yet when he toured North America for his lecture series on aestheticism in the early 1880s; but as he dressed himself flamboyantly and tended to push the envelope with his sardonic and witty manner, he had cultivated a considerable reputation. The Marquess of Lorne, 9th Duke of Argyll and fourth Governor General of Canada, even declined to meet Oscar Wilde lest ongoing rumours of his own suspected homosexuality be exacerbated. All the while, Wilde had not a care in the world what people thought of his effeminacy.

In 1882 (aged 27), he watched a lacrosse match from the Lieutenant Governor’s box in Toronto, Canada, and was said to have remarked to the Toronto Globe newspaper on his great appreciation for “a tall, well-built defence man”. While Wilde had no qualms about public displays of same-sex interactions, having once kissed a waiter in a restaurant (and possibly Walt Whitman too), such actions were unforgivable in the formal courts back in England.

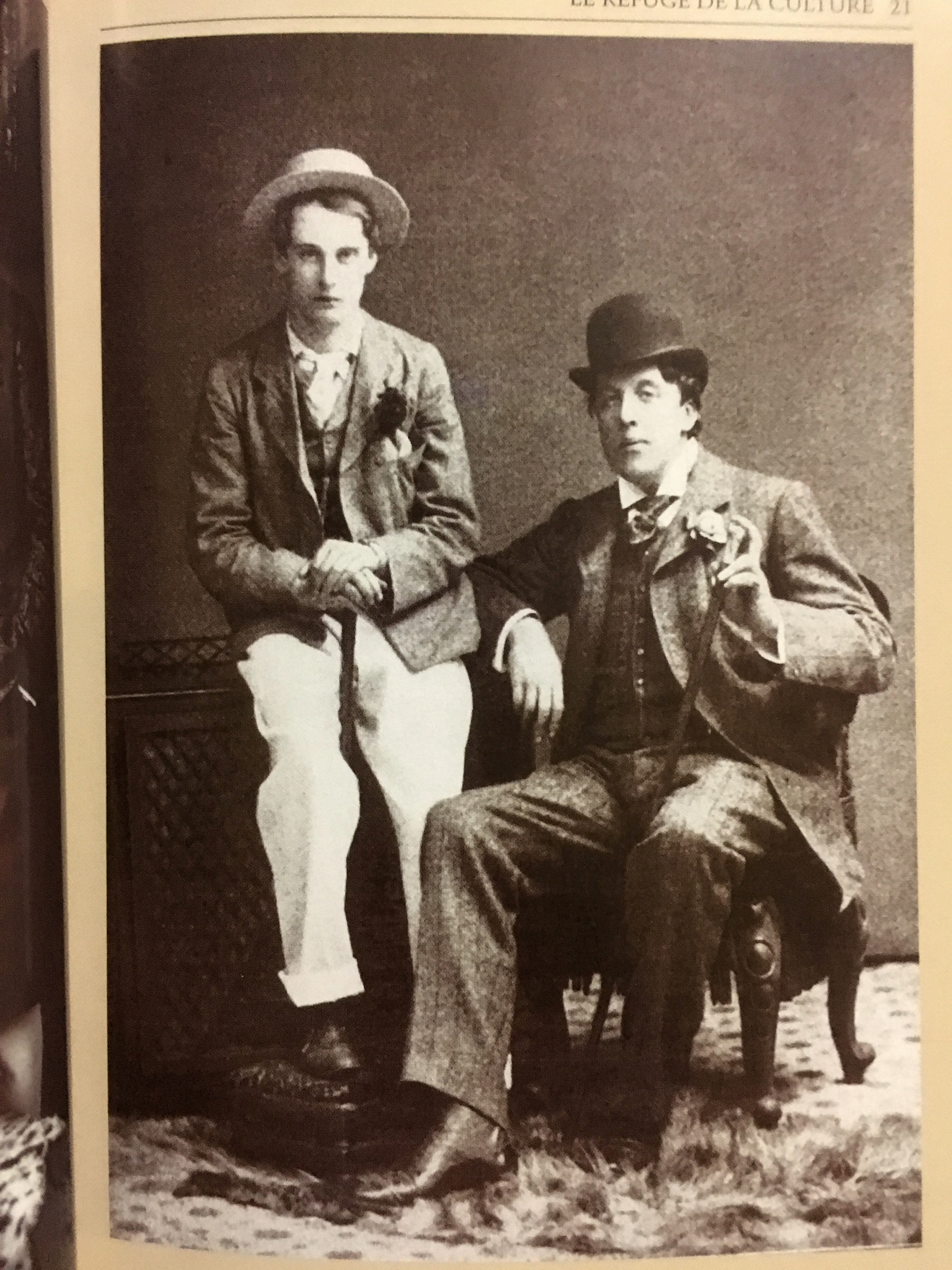

Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, Oscar Wilde’s most famous lover, wrote a poem titled “Two Loves” (1894), which ends with the phrase “I am the Love that dare not speak its name.” The line was used against Wilde in his trial when he was charged by Douglas’ father, the Marquess of Queensberry, who suspected the two gentlemen’s romance and abhorred it. Queensberry demanded that Wilde cut ties with Douglas, persisting despite Wilde’s insouciance.

Queensberry: “I do not say that you are [homosexual], but you look it, and pose at it, which is just as bad. And if I catch you and my son again in any public restaurant I will thrash you.”

Wilde: “I don’t know what the Queensberry rules are, but the Oscar Wilde rule is to shoot on sight.”

An 1894 exchange between The Marquess of Queensberry and Oscar Wilde at Wilde’s residence, 16 Tite Street, London

Unwisely, Wilde pressed charges against Queensberry when the latter left a calling card at Wilde’s club reading “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite [sic]”. Incensed by what he took for a public accusation of sodomy, Wilde sued for libel, but it was this legal action which led to Queensberry’s acquittal and counter-suit against Wilde. Having procured evidence of Wilde’s liaisons with male prostitutes alongside letters to Douglas, Queensberry had cornered Wilde. Douglas’ poem was interpreted as a euphemism for sodomy, which Wilde denied, but evidence was stacking up against him. Out in society, his dandyish reputation and conflicts with Queensberry caused him little harm, but taking the feud to the courtroom proved to be Wilde’s undoing. He was convicted and sentenced to two years’ hard labour. His imprisonment from 1895 to 1897 spurred his decline, and in 1900 he died of meningitis in France – but not before being reunited with Douglas for a time.

In continuing to be himself at all costs, Oscar Wilde was extraordinarily brave in the face of so much discrimination. And yet he had to resort to denying his same-sex encounters in the name of self-preservation. He was incarcerated for his defiance of society’s norms, and he fell from public regard. It wasn’t easy to be queer in the 1890s. Society may have taken strides toward equality and respect since, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy now, either.

What does Wilde’s life over 100 years ago tell us about Pride today? Namely that there are still obstacles to freedom, love, and tolerance, but that the LGBTQ2+ community deserves the right to a parade. Not just the organized Pride parades that take place around the world, but the mere act of parading down the street during day-to-day life: open, out, and free, living authentically without retribution. So-called “Straight Pride parades” happen every single day with the simple privilege of going out into the world without discrimination. The LGBTQ2+ Pride parade should happen every day too – because queer individuals have every reason to be proud.