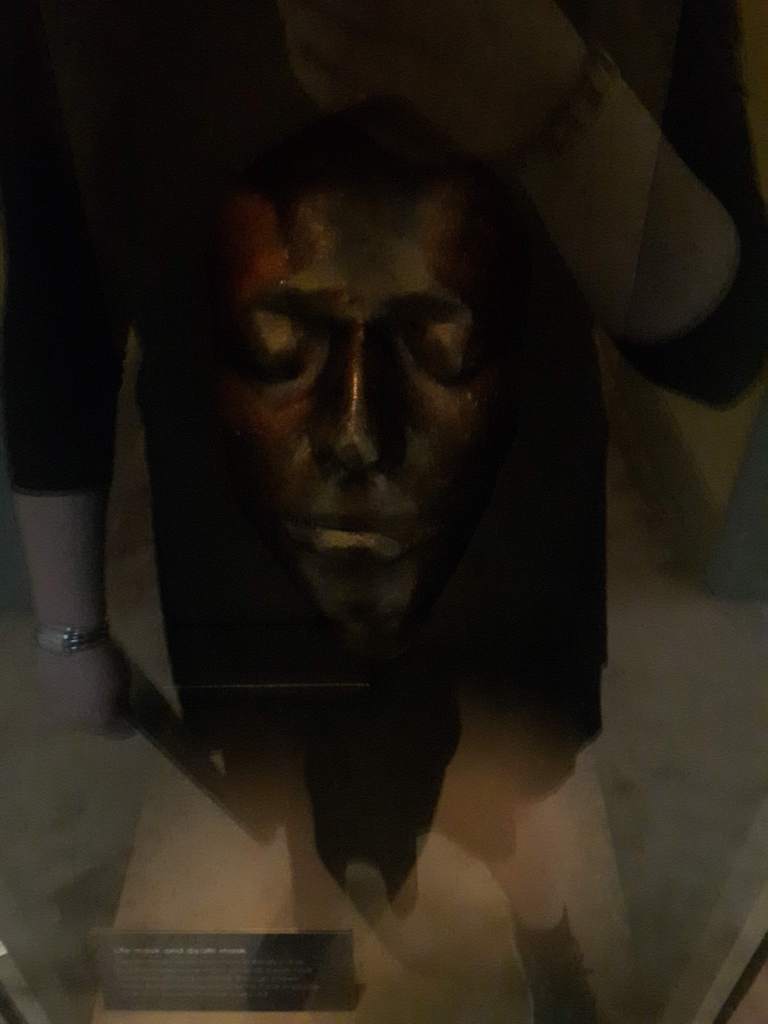

Historically, death masks were used to remember those who had passed away, or to create likenesses in portraits. Life masks are their slightly less macabre twin, and they both close an interpretive gap in physical memory.

When I first set foot in Keats House in Hampstead, London almost exactly a year ago, I had long been fascinated by death masks – but life masks would prove to bring a whole other thrill.

You might wonder why the distinction between the two holds any significance. One type of mask is taken from a deceased subject’s face, while the other involves the face of a living individual. What’s the big difference?

From an interpretive standpoint, the fact that historical figures posed for life masks while living and breathing – that they perhaps might have made a remark or laughed just before the cast was taken – is staggering. The result, while it may seem trifling at the time, is an unrivaled connection to the subject – it outlives them. A life mask of a historical figure preserves their face in its tangible and living form beyond a photograph or painting, allowing us to interact with it.

Let’s give these abstract notions some context. I first came across the poet John Keats (1795-1821) and his work while studying British literature in undergrad. I quickly came to love Romantic poetry, in which nature, emotion, and the metaphysical take centre stage. Keats’ 1820 Ode on a Grecian Urn (in which the speaker marvels at the beauty of an artifact in the British Museum) captures everything I love about museums and literature.

So there I stood in Keats House, ready to connect with my favourite poet in a long-awaited moment of fulfillment. I couldn’t have hoped for a better outcome. For one thing, the house’s interpretation was excellent – I had expected a rather dated presentation of the Romantic poet’s life, but the displays are new, appealing, and most importantly, emotionally evocative. Sensory elements are manifold as we’re given opportunities to visualize Keats’ presence and listen to audio of a first-person interpreter reading his poems and personal writings. And most strikingly, there are masks.

On the ground floor is Keats’ life mask. As a forever fangirl of the poet who lived there from 1818 to 1820, I was instantly drawn to it. (I can’t believe I’m telling you this, because it sounds irredeemably creepy.) My strange urge to reach out for the mask was validated (thank God, I’m not crazy after all!) when I read the label next to it: please touch.

Photo: Serena Ypelaar

And that was how I ended up in Keats’ house touching his face. To further justify my museum nerdiness + mild infatuation, I can only describe the experience as unique and surreal.

With a life mask, you can engage with those who’ve predeceased you, whether you feel the contours of their face or just look. It’s so rare to find this kind of connection with individuals who died before photography gathered steam. Maybe Keats House really knew their audience, but the experience far surpassed trying to picture someone’s face based on portraits: here was the unembellished truth of what Keats really looked like. Since no photographs of him exist, the mask is an invaluable instrument of truth.

Upstairs was a much more sobering reality, but affecting all the same. The lighthearted yet poignant discovery of the life mask was now replaced by a sombre shift: here, behind glass, was Keats’ death mask. Keats died of tuberculosis aged 25. The difference in his face was noticeable. His once robust features were gaunt and thinner, a mark of the illness that claimed his life; and like the life mask, coming face to face with Keats (now in death) was jarring. It’s appropriate that this iteration was inaccessible by touch, for obvious ethical (and perhaps even spiritual) reasons. No one needs to touch a death mask, unless they’re a collections manager! Regardless, I was glad to have the rare privilege of seeing both a life and death mask of the same person, however grim the comparison.

Life and death masks offer an indisputable connection to the subject(s) of both. The concept is a goldmine as far as historical and biographical interpretation goes. In front of us is the near-objective image of a person’s likeness, almost as if they were before our eyes. One thing’s for sure: when looking at Keats’ life mask, I felt as mesmerized as the speaker looking at the Grecian urn in the British Museum – viewing a moment in time. I hope to see more life (and death) masks of public figures in the future, because their immersive value is priceless.

When old age shall this generation waste,

John Keats, from “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (1820)

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty — that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”