As we spend our days in isolation and uncertainty, we thought it fitting to revisit the poems of Emily Dickinson, who led a singular and solitary life, reminding us of the importance of maintaining a rich inner world.

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) spent the majority of her life in and around her father’s homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts, where she lived and died in relative seclusion. She never married, rarely travelled, and most of her interactions with people occurred through letters and other correspondence. By the final years of her life, she barely even left her bedroom.

If that sounds familiar to you, you’re not alone. Nowadays, while a pandemic sweeps the globe, most of us spend our days confined to our bedrooms or our living rooms, only interacting with those we care about from a distance. Technology helps, to be sure. But there’s no doubt that a lot of us are feeling isolated and anxious during this uncertain time. Who better to turn to for some solace than Emily Dickinson?

Maureen N. McLane calls Dickinson “a homegrown poet of terror, abjection, and difficulty.” Dickinson often wrote about death and the nature of consciousness, the negation of self and the discomfort of being a body in the world.

She was no stranger to solitude. In a letter to her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert, Dickinson wrote: “I would paint a portrait which would bring the tears, had I a canvass for it, and the scene should be—solitude, and the figures—solitude—and the lights and shades each a solitude. I could fill a chamber with landscapes so lone, men should pause and weep there; then haste grateful home, for a loved one left.”

There’s a lot of debate about why Dickinson self-isolated, whether it was by choice or whether she was forced into seclusion due to illness of some kind (mental or otherwise). But I like what poet Adrienne Rich supposes: “I have a notion that genius knows itself; that Dickinson chose her seclusion, knowing she was exceptional and knowing what she needed. It was, moreover, no hermetic retreat, but a seclusion which included a wide range of people, of reading and correspondence.”

Dickinson chose seclusion because that’s what she needed in order to write the astonishing 1,789 poems she left behind.

And what her poems reveal is a sharp-witted, fierce, intelligent woman, who reinvented poetic form and carved her own path in life to the bewilderment of those around her. In short, her poems reveal the vastness of a rich inner life, something we could all work to cultivate during this time. When your external world is limited to a small town, or as is the case for many of us now, to house and home, then our inner worlds become our most important dwelling places. Per Dickinson:

The Brain – is wider than the Sky –

For – put them side by side –

The one the other will contain

With ease – and You – beside –(632)

The mind, to paraphrase Milton, is its own place and can contain the whole sky or sea or anything besides, including you and me and everyone we know. Its capacity for imagination and wonder and expansive thought is unfathomable. More than this, our minds give us the ability to read and think and empathize with others, allowing for the expansion of our inner world.

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry –

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll –

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human Soul –(1263)

Poetry is exceptional in its capacity to transport us. Through her imagination and her poetry, Dickinson could traverse any distance. By returning to her poems, and following her example—her keen observation of the beautiful details of her immediate world and her willingness to look within herself for substance and meaning—we might make the distance we all feel right now a little more bearable. After all,

Distance – is not the Realm of Fox

Nor by Relay of Bird

Abated – Distance is

Until thyself, Beloved.(1155)

Here, Dickinson tells us that distance is not about physical space, the lengths a fox or a bird can travel. But the final line is tricky to decipher. Dickinson delights in ambiguity (“Tell all the truth but tell it slant”), taking her readers to a place where meaning loses stable footing. “Distance is / Until thyself, Beloved” could mean that distance is nothing more than the space between the speaker and their beloved. But “thyself” could also be an address to the reader or to the speaker herself, suggesting that physical distance pales in comparison to metaphysical distance, the distance that we feel within. Knowledge of self, having an inner life as sharp and imaginative as Dickinson’s, is how we really overcome distance. And we will overcome this distance.

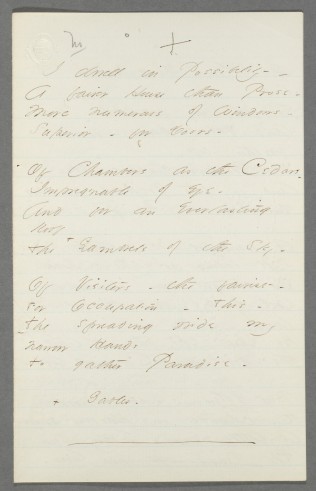

Dickinson sums it up best in one of my favourite poems:

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –(657)

Although we remain confined to our houses, Emily Dickinson shows us one way, at least, that we might use this time to dwell not in the physical isolation we feel, but in the inherent possibility of our own minds.