Hello again, dear readers, and thanks for visiting The Mindful Rambler! Last week, we talked about history and who writes our past. Collectively (though not without knowledge hierarchies), we shape our memory of historical events through storytelling. Now, let’s look at the second of our four themes: Literature.

When I speak broadly about literature, I mean fictional prose, poetry, literary essays, or the like. Literature may not necessarily reflect on actual events, but it does capture elements of the human experience for us to examine and reflect upon. Thus, literature is an instrument of storytelling.

Why is it important to look at literature in the field of interpretation? Because literature itself is an interpretation of the world around us. The creators of literature are absorbing what they see around them and reproducing (or subverting) it through the act of storytelling. Drawing upon shared experiences and portraying them, whether through realism or abstraction, allows us to understand each other, ourselves, and our environment.

Literature uses the written word to tell us the truths the world doesn’t share openly – but it’s more than just that. Books, poems, pamphlets, essays, and other literature aren’t limited to just words. They give us imagery; they provoke our senses and prompt us to think critically in response to stimuli. We aren’t force-fed these images, nor is the meaning of a literary work meant to slap us in the face. There are nuances that we ourselves have to read into, which often means that we as individuals bring different perspectives to the literature we consume.

In the act of reading, we’re interpreting. We process the messages that writers (who have interpreted before us) present to us, and our takeaway varies from one person to the next based on past experiences. Our own personalities and backstories define what stands out to us and what we think is worth considering.

So how do we find a definitive interpretation of literary texts?

We can’t.

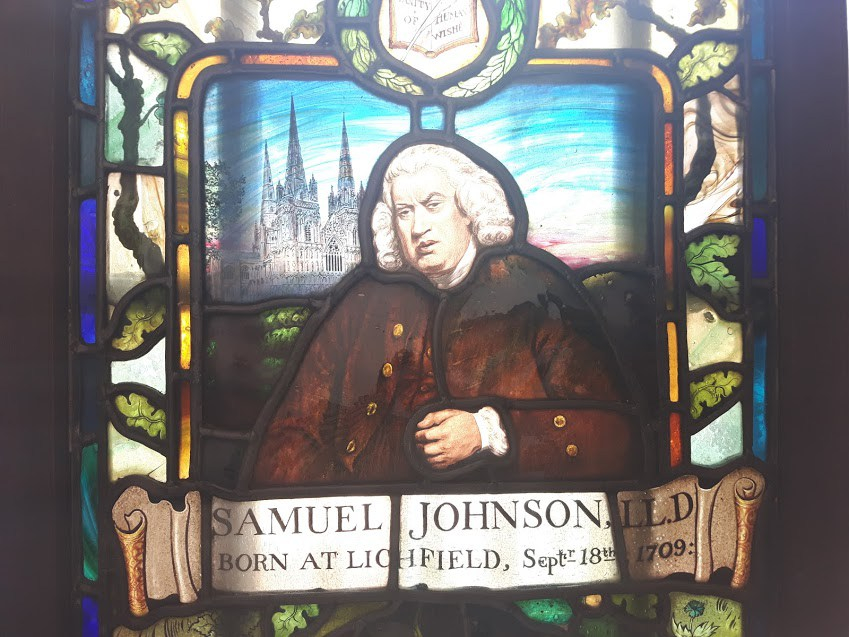

We can choose to venerate the analyses of certain individuals – for instance, since I like Samuel Johnson, to whom this blog’s title pays homage, I’m more likely to embrace his opinions on Shakespeare. Conversely, if I love Jane Austen (and I do, most ardently), I will reject Mark Twain’s scathing criticisms of Pride and Prejudice. But you, or someone else, may like and respect Twain’s opinion and therefore lend it some credence. Our biases influence our perceptions, so interpreting literature is a constant decision-making process.

Hence, once literature is published, its meaning lies in the hands of the recipient. Authors’ intentions are powerful and significant, and this column, “On Literature“, will explore those ethical concerns. However, we aren’t necessarily bound by them. No one can really police our response to literature because it’s a very personal interaction. As a former English major, I definitely learned how to pick up on people’s partiality and respond to that, but ultimately, we form our own relationships with the materials that are presented to us.

So literature as media is oddly empowering: we can choose what we read, how we read it, and how we respond to it. We can be mindful of the contexts in which a work was produced, or we can simply read it at face value – and is either interpretation wrong?