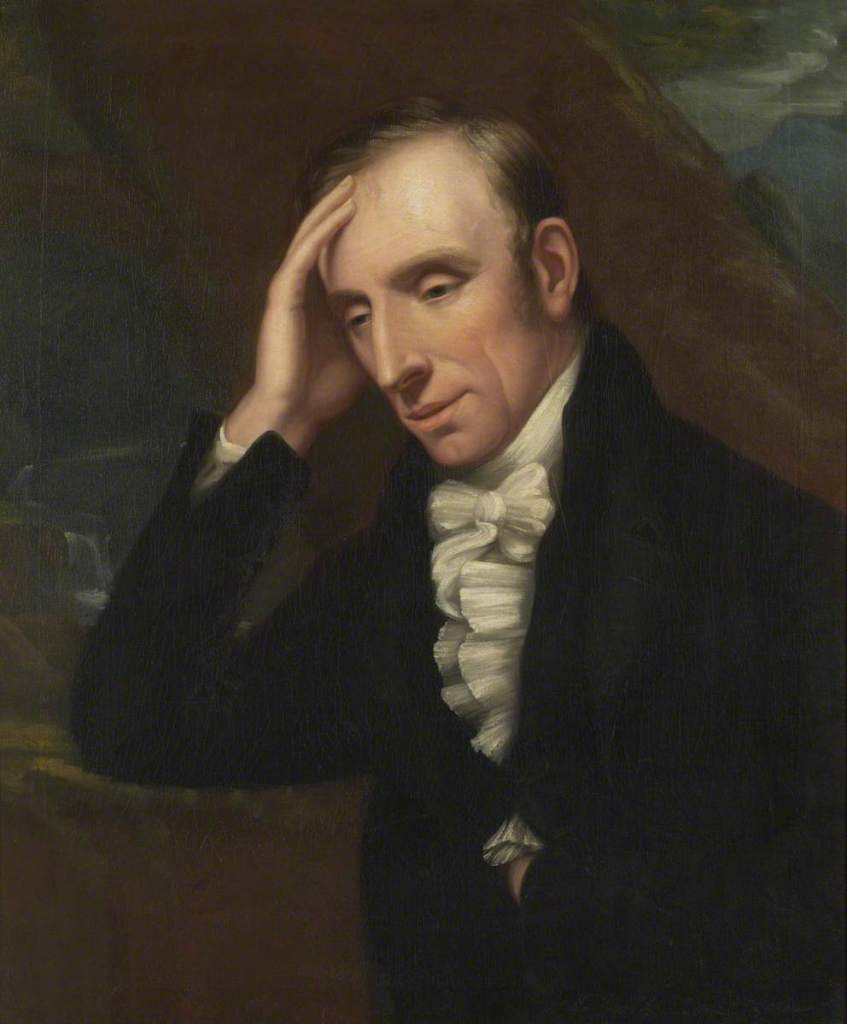

It’s the 250th anniversary of Romantic poet William Wordsworth’s birth, and his love for nature continues to resonate with contemporary audiences.

When I learned that April 7th was the 250th birthday of Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850), I knew we had to tribute his legacy in some way. And what’s the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of Wordsworth’s poems?

That’s right: nature.

As we isolate ourselves these days, it’s easy to feel lonely. But it seems that many of us have turned to nature as our saving grace. Nature is known to boost mental health and well-being – and now, when we’re unable to go to public places, a solo walk outdoors can do us a world of good.

William Wordsworth and his fellow Romantic poets John Keats, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, and Robert Southey professed a profound regard for nature. So what better time to celebrate one of the most famous English writers of all time (and a personal favourite) than now, as we rely on nature to preserve our sanity? The timing of the #Wordsworth250 commemoration may seem unfortunate, but it’s also rather apt. Though events scheduled in the Lake District and northwestern England for the year-long celebration have been cancelled or moved online due to the COVID-19 crisis, that doesn’t mean we can’t still enjoy the works of England’s former Poet Laureate.

Nature’s offerings are bountiful: fresh air, tranquil scenery, ambient sounds and smells. It’s no wonder humans worship nature, in a sense. In remembering Wordsworth, we can appreciate how eloquently he conveys his love of nature, to which I’m sure many of us can relate. The sense of connection we derive from our shared love of nature provides us with some common ground, as the human experience is an integral element of Romantic poetry.

Interestingly enough, Wordsworth wrote much of his most famous work, The Prelude (1799), during a time of intense stress and loneliness while living in Germany. It was intended as part of a larger work titled The Recluse, which was never finished. I think the theme of isolation throughout Wordsworth’s poetry holds some relevance to our current situation, a consoling thought for anyone reading poems alone in their room (ahem, me).

Wordsworth is well-known for his ability to take readers through countryside rambles, using sensory imagery and lines heaving with emotion. His descriptions are vivid but also abstract, allowing us to travel to a site ourselves. Wordsworth’s Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey (1798) does just that. Upon reading, we’re transported to the landscape above the Abbey, taking in the lush scenery and sublime beauty of nature through the experience of the speaker.

And I have felt

William Wordsworth, “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey” (1798), from lines 93-105

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Wordsworth lets us witness the scene (and the speaker’s relationship with it) as if we were there too. How does he do this? Through senses and the imagination. Wordsworth saw imagination as a spiritual force. Famous for invoking the power of the sublime – whereby words incite thoughts and emotions beyond the ordinary – Wordsworth confronts the metaphysical, exploring concepts of time, space, knowing, and being. It can therefore reassure us to escape into nature through his words on the page. So even when we can’t walk through the countryside, we can see, smell, and hear it so convincingly as if we are there – through imagination.

Why do we love interacting with nature so much, anyway? Here we’re shown how rejuvenated Wordsworth’s speaker feels to be out of doors observing the ruins of Tintern Abbey:

These beauteous forms,

Wordsworth, lines 22-30

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man’s eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din,

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind,

With tranquil restoration: — feelings too

Nature awakens our senses through sights, sounds, smells, and even touch – sitting in the grass, or feeling the wind lift your hair. Wordsworth was a master at evoking these sensations in his poetry, which is why he’s lauded as one of the most iconic British poets of all time – we really do feel his experiences as if they could be our own. In the year of Wordsworth’s 250th birthday, the pull of our individual relationships with nature still holds weight with readers worldwide.

I’m an ardent fan of Romantic poetry at the best of times (if you couldn’t already tell). But despite the slant of my own opinion, if you’re feeling cooped up, I encourage you to check out Wordsworth’s poems and marvel at the splendour of nature. Perhaps his works will inspire you to take a solitary walk outdoors, or maybe you’ll go there from the comfort of your living room – but either way, you might just feel transported for a while.

After all, there’s nothing quite like a change of scenery to refresh your mind and soul. In remembering Wordsworth, we can do just that.

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

Wordsworth, from lines 134-146

For all sweet sounds and harmonies; oh! then,

If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,

Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy wilt thou remember me,

And these my exhortations!