Starring Jason Momoa, Frontier explores the pluralistic conflicts defining Canada’s fur trade in the late 18th century. From a historical and ethical perspective, how does the show’s cultural authenticity stack up?

Warning: this article contains light spoilers about events depicted in Frontier.

It’s often said that there are two sides to a story.

But that’s not true: there are many sides to a story, and Frontier proves it’s possible (though difficult) to tell them.

I’ve been waiting to write about Frontier since before The Mindful Rambler was founded. Anyone who knows me knows I have an enduring love for early Canadian history … and in 2016, Discovery Channel and Netflix miraculously created a television show about it!

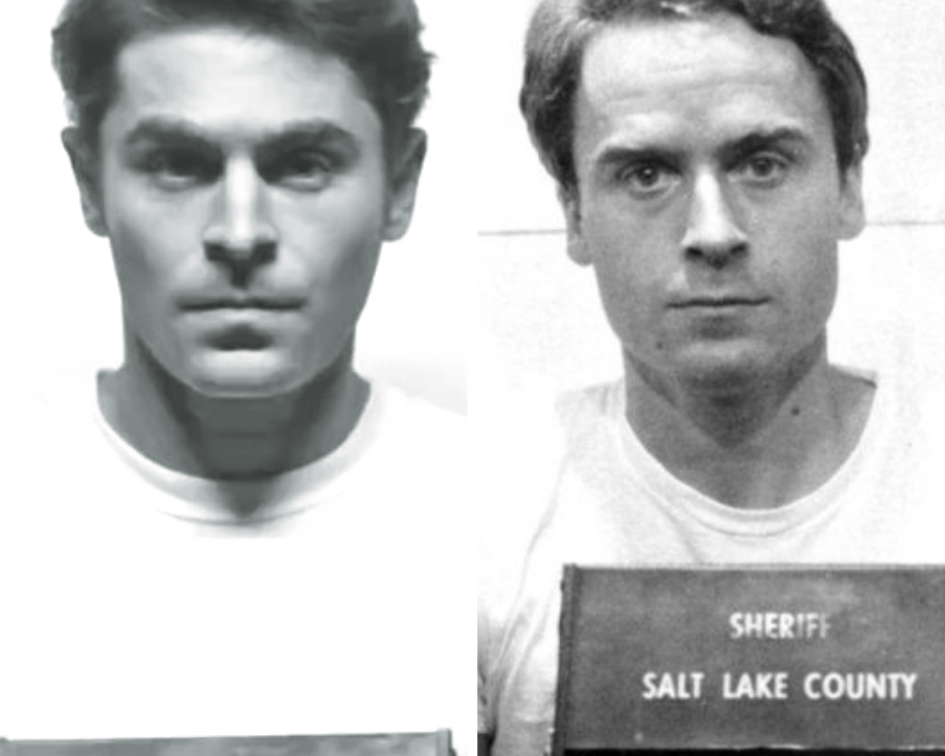

Set in the late 18th century in what is now Canada, Frontier centres on locations such as Hudson Bay, James Bay, Montréal, Fort James, and the wilderness. Indigenous peoples have lived on the land since time immemorial, long before European settlers arrived – a fact which is starkly portrayed in the series. The show stars Jason Momoa (also Executive Producer) as Declan Harp, a half-Cree, half-Irish trader who, for deeply personal reasons, seeks to destroy the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)’s oppressive monopoly on the fur trade.

There’s a plethora of “New World” films/shows out there, many of which are inevitably framed from the perspective of newly arrived colonial settlers. But it’s not inevitable to tell the story that way. Frontier is an example of what happens when you incorporate multiple perspectives and, crucially, spend time on authenticity. Though its storytelling and pacing is less than perfect, Frontier‘s diversity and inclusion is noteworthy and fairly well-done.

Indigenous and pluralistic representation

Today, Canada is populated by diverse cultural and linguistic groups, which was also the case during the 1770s. Frontier showrunners Brad Peyton, Rob Blackie, and Peter Blackie take care not to fall into the trap of depicting Indigenous peoples as one and the same – throughout its three seasons, we’ve seen Cree, Haudenosaunee, Métis, Inuit, and more nations – acknowledging that they do not comprise just one singular culture or identity.

Whenever I talk about Frontier and Jason Momoa playing an Indigenous man, people often ask “but isn’t he Hawaiian?”

“Yes, Momoa is part Native Hawaiian, but he’s also part Native American on his mother’s side,” I say. You’d be surprised how skeptically people react to that answer. There’s a definite issue with saying someone is not “_________ enough” to identify with their heritage (I know from experience, as a mixed individual). To say that anyone who is part First Nations, part Inuit, etc. isn’t “Indigenous enough” is akin to telling a mixed English/Scottish Canadian that they aren’t allowed to identify as Scottish. People who are part Indigenous are Indigenous and have a right to their culture.

Momoa is heavily invested in sharing the experiences of Indigenous peoples in North America. Though working in London at the time, he was vocal during the #NoDAPL protest in North Dakota in 2016; he also starred in Road to Paloma (2014), which exposes the systemic dangers to Indigenous women in the United States. And now, on Frontier, he’s helping portray Canadian history from an Indigenous vantage point. Momoa’s Instagram posts demonstrate how he advocates for Canadian history as I’ve never seen in another American. His work in Frontier contributes to the preservation of Canadian history from multiple perspectives.

Frontier also emphasizes linguistic diversity. Métis/Saulteaux-Cree actress Jessica Matten, who plays Harp’s sister-in-law Sokanon, learned two specific Indigenous languages for the show:

I’m mainly speaking Swampy Cree and also Ojibway to reflect Sokanon’s eclectic upbringing, born an Ojibway woman but raised amongst Métis, Cree, Scottish, French people on Turtle Island [North America] …

Jessica Matten, Instagram post

Matten also provided creative direction in depicting the sale of Indigenous women to white settlers (as “country wives”). The portrayal of these realities mirrors today’s issues with missing and murdered Indigenous women.

In early North America, intermarriage also occurred and is portrayed in Frontier, another nod to authentic representation. Irish settler O’Reilly’s wife Kahwihta is Haudenosaunee (married under frankly sinister circumstances), and Sokanon and Michael Smyth (Landon Liboiron)’s budding yet troubled romance reflects the effects of the influx of fur traders on traditional lands. Nevertheless, Indigenous women – and almost all the women on the show – are depicted not as helpless victims but as clever and resourceful fighters. Frontier doesn’t shy away from the HBC’s violent behaviour that caused lasting trauma and grief for Indigenous peoples either, as depicted in the opening of season three, when the HBC is shown raiding and assaulting a Métis village.

Even amidst the fur trading companies, pluralism is the name of the game. There’s Declan Harp’s Métis-fronted Black Wolf Company, working directly against the HBC. The Scottish Brown brothers (Allan Hawco – also Executive Producer – and Michael Patric) are rivals to Carruthers & Co., managed formidably by Elizabeth Carruthers (Katie McGrath) after her husband’s death. Samuel Grant (Shawn Doyle) and Cobbs Pond (Greg Bryk) are Americans established in Montreal, and Michael Smyth, an impoverished Irish stowaway, joins Harp’s company. Englishman Lord Benton (Alun Armstrong), a fictitious governor of the HBC who loosely represents the company’s real-life actions, is portrayed mercilessly – on Frontier, the HBC is held accountable for its historical misdeeds.

The show flounders in its portrayal of Black loyalists in Canada, however. Charleston (Demetrius Grosse) flees enslavement in the United States and falls in with Harp, but he is (SPOILER ALERT) the first to die in an overseas voyage – a typical trope in Hollywood movies (Black Dude Dies First trope). The two Black characters only play supporting roles; Josephette (Karen LeBlanc) is a close associate of Elizabeth Carruthers (Katie McGrath) but eventually takes on the bulk of the company management when Elizabeth’s new husband Douglas Brown (Allan Hawco) drives it into the ground. If Josephette were given a larger role, her character could thrive in the limelight.

A new Frontier for Canadian history

While Frontier is undeniably flawed, both in a storytelling/pacing sense and an accuracy sense, I think its merits outweigh its detractors. The show illustrates (and popularizes) a long-distant era of Canadian history and emphasizes the facets of the fur trade economy. Most importantly, without glorifying colonialism, it depicts the conflicting interests of the different individuals and groups trying to live off the land – and in some cases, exploit it. It features Indigenous languages, celebrates women’s autonomy, and inspires awe – there was a lot going on in the Hudson Bay region.

Warts and all, Frontier proves that Canadian history is by no means boring.