The autobiography is a curious means of presenting one’s life story, one that allows for filtration and condensation into a story as engaging as the author (the self-biographer) desires.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about autobiographies, in which someone illustrates their own life by selectively exploring episodes of their past. There’s a certain kind of autonomy in fashioning one’s own life story for public consumption, in which we can filter out certain aspects like a sieve. Maybe we don’t want unflattering elements of our lives to reach the eyes and ears of others – but would that be as compelling a story?

If we don’t admit our failures, conflict, setbacks, surprises, embarrassments, and other negative experiences, what shadow of ourselves are we presenting? The phenomenon of “self-fashioning” is all the more relevant to us in the twenty-first century, since Instagram and other social media rule the day. Our Instagram pages are curated galleries of our identity, but they’re only the tip of the iceberg, an infinitesimal slice of our actual lives. They nevertheless create an impression that lasts, especially when we don’t often see someone in person. Short of communicating with them directly, we’re left with what they present to us on social media, a public front that one can’t call balanced. This controlled presentation is like a darkened room that only allows light through tiny cracks – the cracks being the posts we decide to share.

British novelist Sophie Kinsella recently released a book titled My Not So Perfect Life (2017) which focused on the warped perceptions of our lives and others’ thanks to social media. Kinsella has encouraged readers to share less-than-perfect moments of their lives on Instagram and to celebrate them as a typical facet of the human experience. But the persistent insincerity of Instagram mirrors the ability of formal autobiographies to stretch, filter, and warp the truth. When publishing on social media, we’re sharing only the parts of ourselves that we want the world to see.

Lemony Snicket provides another, albeit exaggerated view into self-fashioning: his Unauthorized Autobiography (2002) is a dramatized example of how the autobiography is a tool of self-invention. Lemony Snicket is in fact a fictitious character (created by American author Daniel Handler) credited with chronicling the lives of the also fictional Baudelaire orphans. Likewise, Snicket’s autobiography represents the lengths that we can go to in order to construct and manipulate identity on a public platform.

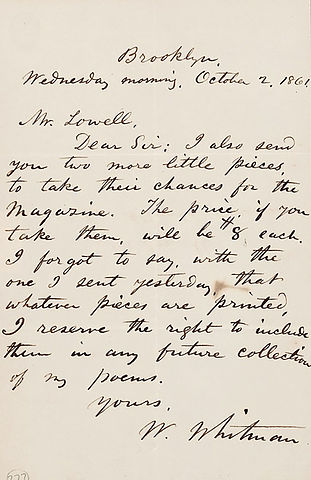

Whether or not we’re actually writing a formal autobiography, we are authoring our identity every day, inventing our public face based on how we act and what we share. When documenting that identity, we can and should carry an awareness of how we will be perceived by others not only today, but in the future. In the practice of history, for instance, we try to understand people who have predeceased us based on records left behind; it’ll henceforth be interesting to see how historical analysis proceeds in the digital age.

The true self, the one we are when we are alone, only has one audience member: ourselves. Our true identity is beyond communicating with others because there are so many layers to such an identity; so we’re burdened with the responsibility of choosing how we present it to the world. The question is, will we favour authenticity or will we compete on the basis of concealing our very human flaws?