Though storytelling is highly personal, it thrives on human interaction and the sharing of experiences, making storytelling and interpretation inherently collaborative processes.

“You can’t control what others think, but you can control what you put out there.”

This idea is something a lot of people carry around, and it has a special relevance when we think of how we’re surrounded by stories. As we enter a brand new year of The Mindful Rambler, I’d like to reframe the discussion on storytelling and interpretation – and the methods of both processes – which we’ve been examining here on the blog.

In telling a story, whether it’s for entertainment, healing, documentation, critical analysis, or otherwise, there’s always a lot of pressure around how it will be received. Will people like it? Will they get it? Will they take from it the information you’re hoping to impart?

Photo: Giphy

I experience that pressure whenever I write something. Anything I write can be interpreted, misinterpreted, and reinterpreted, and the truth is that my writing won’t exist entirely under my control once it’s out there. Every person who hears a story brings their own unique experience to it, creating something new. Two people who read the same book, for example, might see it in completely different ways, meaning that the result – the experience of storytelling – actually becomes a hybridization, a meeting place between the “teller” and the “listener”. Storytelling is the act of bringing one’s story, through words, images, sound, and other sensory outputs, into being outside of one’s self.

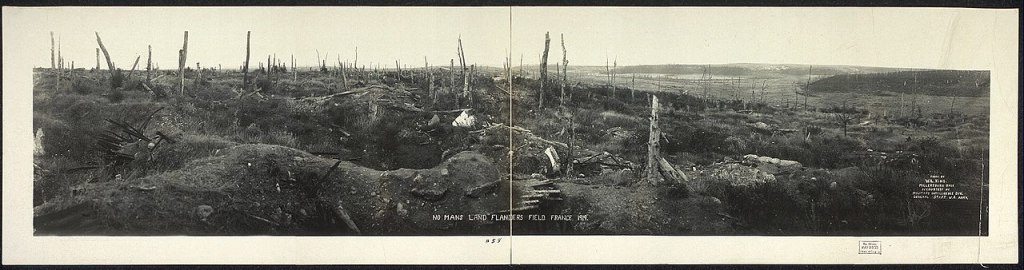

To avoid delving too far into the abstract, I’ll use an example. If someone is describing a place while telling a story, they’ll describe it as best they can noting features they feel are important to the story or of personal value to them. The person listening to the story will then construct their own interpretation of the event, incorporating their past experiences, feelings, biases, and assumptions. In short, the story is changed by the listener’s reception of it. Every single person hearing that story will have a different conceptualization of it, and a different understanding.

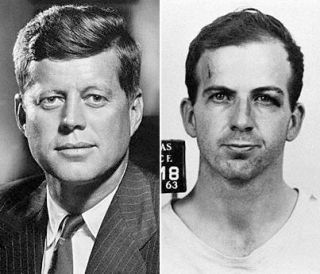

It’s the same with novel writing. Writers describe a character, for instance, and we, the readers, each construct a mental image of that person (and then get angry when the film casting doesn’t match that). I don’t know how many people I heard, back in middle school, ranting about how they definitely, totally did not picture Robert Pattinson when they dreamed up Twilight’s Edward Cullen in their heads. There are also race-based biases toward literary characters which often become clear when a person of colour is cast as a character many assumed would be white (like the vampire Laurent from the same franchise), racial prejudices becoming evident with readers’ indignation.

Irrespective of a story and its content, creators must become comfortable with the notion that each person who hears their story is going to see something different. There’s no way a storyteller can construct their tale in a way that guarantees uniform interpretation. Attempting to do so can result in over-describing something and alienating readers by unconsciously (or consciously) trying to harness control over their perceptions. It’s possible to use photographs to aid a visual picture, for instance, but these will still foster further imaginings on the part of the listener. Gaps in information will be filled independently – so the point is not to describe every single thing that is within you, but rather what is important to the story. That’s how we get such engaging stories, whether in literature, history, entertainment, art, memoir, or otherwise. Allow the listener to meet you halfway, and together you can share the experience while expressing trust in another person.

Maybe that’s why storytelling is so important to us – on an instinctual level, it allows us to connect with each other and find common ground.